Sunstein Insights

Trademark Lesson Ripped from the Headlines: Trump Team Books the Wrong Four Seasons

Did the Trump campaign really mean to book Four Seasons Total Landscaping in Philadelphia and not the Four Seasons Hotel? And how can one city have two Four Seasons? Who would have thought, of all things, that these would be the questions on everyone’s mind as this year’s titanic presidential contest came to a dramatic close on Saturday afternoon? We may never know the answer to the first question, but the answer to the second question touches on an important principle of trademark law: not all instances of actual confusion between two similarly named businesses rises to actionable confusion that can be remedied by U.S. trademark law.

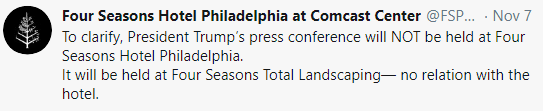

Four days after the 2020 presidential election President Donald Trump announced on Twitter that there would be a “Lawyers Press Conference at Four Seasons, Philadelphia. 11:00 A.M.” Soon thereafter President Trump returned to Twitter to clarify that the press conference would not be taking place at the Four Seasons Hotel, but instead at the similarly named Four Seasons Total Landscaping.

Calls from interested attendees soon began flooding the Four Seasons Hotel asking the hotel to confirm that the conference would be taking place there. But the hotel directed the press to the landscaping business and confirmed on Twitter that the landscaping company has “no relation with the hotel.”

Soon thereafter, at 11:30 am on Saturday, the domestic and international press assembled outside a garage door at Four Seasons Total Landscaping to hear from President Trump’s attorneys, including the former mayor of New York, Rudy Giuliani, to discuss the Trump campaign’s claims of voter fraud in the presidential election. One could hardly think of a more important topic with greater legal and political implications for the future of the United States. So why did this conference take place outside a landscaping business on the outskirts of Philadelphia? The likely answer is by mistake.

On Twitter and in online articles journalists have been speculating that someone affiliated with the Trump campaign mistakenly booked the Four Seasons Total Landscaping business instead of the better-known Four Seasons hotel. The conclusion that this was all a big mistake seems inescapable if you consider that Four Seasons Total Landscaping is on the same block as a crematorium and an adult bookstore and nothing in the content of any speech given on Saturday suggested a tie-in to the location.

U.S. trademark law exists to protect consumers from confusion that may occur when two similarly named businesses exist in a geographic area. So why does the law allow the Four Seasons Hotel and Four Seasons Total Landscaping to co-exist? The short answer is that trademark law is designed to eliminate situations where there is a likelihood of confusion, but it is not designed to safeguard against every situation in which someone is actually confused, especially when that person is acting quickly or with less mental acuity than a normal consumer might.

When comparing any two trademarks the law encourages weighing a number of factors to determine whether there is a likelihood of confusion. Chief among these factors is a comparison of the similarity of the marks and the relatedness of the goods and services at issue. The two trademarks here both contain the same beginning part “Four Seasons” and end with words that describe the nature of the business, “Hotel” and “Total Landscaping.” A comparison of the marks alone might lead to a belief that the businesses are somehow related or affiliated since the most distinctive portion of each mark is shared.

However, the likelihood of confusion test requires the fact-finder to weigh whether the services at issue, in this case hospitality services and landscaping services, are related enough that people might believe the businesses are linked. If the goods and services are not related it is less likely that consumer confusion will ensue. This is true even where the marks are the exact same, such as with Delta Airlines and Delta faucets. A reasonable consumer is unlikely to believe the two Deltas are affiliated, because their product offerings are so different. The fact that both Four Seasons appear to have been operating in the Philadelphia market for close to 30 years without (so far as we know) prior issue only bolsters this conclusion.

In this situation, of course, someone was actually confused. It is likely that the Trump campaign intended to book conference space at the Four Seasons Hotel, yet they booked space at Four Seasons Total Landscaping. An instance of actual consumer confusion such as this is only one of the many factors of the likelihood of confusion test. The test requires a thought-experiment as to whether it is likely that, for instance, someone who was looking to book a conference room would call a landscaping company. Until this past weekend, it was easy to conclude that such a possibility would be extremely remote.

If Four Seasons Hotel could prove that a large number of people who were seeking its conference services ended up booking their conference at Four Seasons Total Landscaping, they may be able to prove that the two marks are likely to be confused, but the fact that someone acting under significant time pressure was confused, once, is generally not sufficient. Courts in the U.K. have referred to someone in a similar situation as a “moron in a hurry.” First used in the 1978 case Morning Star Cooperative v. Express Newspapers, showing that morons in a hurry are confused is not generally sufficient, without more, to show likelihood of confusion.

Some marks are so famous that U.S. trademark law bars third party use of the famous mark on even wildly divergent goods and services. More specifically, the law allows owners of famous marks to forbid use by other parties that would lessen the uniqueness of the mark. However, to qualify for this protection a mark must be very famous; put another way, the brand must be an instantly recognizable household name at the level of Coca-Cola, Tide, or Starbucks. It is not clear Four Seasons Hotel has risen to that level, and as the news demonstrates, Four Seasons Hotel already co-exists in many cities with other businesses that use the Four Seasons mark.

U.S. trademark law exists to protect consumers from confusion that is likely to occur when two similarly named businesses exist, but the law does not provide a remedy every time one person happens to be confused, even if that person serves the President of the United States.

Most Popular

-

Massachusetts Jury Sets New Record Under Federal Defend Trade Secrets Act With $452 Million Damages Award

-

New Trademark Office Fees Increase Cost, Headaches

-

The New York Times v. OpenAI: The Biggest IP Case Ever

-

Advertisers Beware: Falsely Advertising Products as “Patented” and “Proprietary” Can Violate the Lanham Act, Says the Federal Circuit

-

Corporate Transparency Act: To File or Not to File?

-

Wavy Baby Waves Goodbye to its Attempt at Humor

We use cookies to improve your site experience, distinguish you from other users and support the marketing of our services. These cookies may store your personal information. By continuing to use our website, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device. For more information, please visit our Privacy Notice.